- Home

- McCauley, Kirby

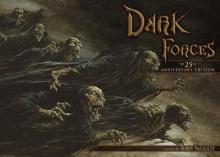

Dark Forces

Dark Forces Read online

Dark Forces

25th anniversary edition

edited by

Kirby

McCauley

Cemetery Dance Publications

Baltimore

2011

25th Anniversary Edition of Dark Forces copyright © 2006, 2011by Kirby McCauley

All Rights Reserved.

Manufactured in the United States of America.

Cemetery Dance Publications, 132-B Industry Lane, Unit #7, Forest Hill, MD 21050

Dark Forces copyright © 1980 by Kirby McCauley

First published by The Viking Press, 625 Madison Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10022

First Digital Edition

ISBN: 978-1-58767-274-3

“Mark Ingestre: The Customer’s Tale” copyright © 1980 by Robert Aickman

“The Night Before Christmas” copyright © 1980 by Robert Bloch

“A Touch of Petulance” copyright © 1980 by Ray Bradbury

“Dark Angel” copyright © 1980 by Edward Bryant

“The Brood” copyright © 1980 by Ramsey Campbell

“The Late Shift” copyright © 1980 by Dennis Etchison

“The Stupid Joke” copyright © 1980 by Edward Gorey

“A Garden of Blackred Roses” copyright © 1980 by Charles L. Grant

“The Crest Of Thirty-Six” copyright © 1980 by Davis Grubb

“Lindsay and the Red City Blues” copyright © 1980 by Joe Haldeman

“The Mist” copyright © 1980 by Stephen King

“The Peculiar Demesne” copyright © 1980 by Russell Kirk

“Children of the Kingdom” copyright © 1980 by T. E. D. Klein

“Where There’s a Will” copyright © 1980 by Richard Matheson & Richard

Christian Matheson

“The Bingo Master” copyright © 1980 by Joyce Carol Oates

“The Whistling Well” copyright © 1980 by Clifford D. Simak

“The Enemy” copyright © 1980 by Isaac Bashevis Singer

“Vengeance Is.” copyright © 1980 by Theodore Sturgeon

“Where the Stones Grow” copyright © 1980 by Lisa Tuttle

“Where the Summer Ends” copyright © 1980 by Karl Edward Wagner

“Owls Hoot in the Daytime” copyright © 1980 by Manly Wade Wellman

“Traps” copyright © 1980 by Gahan Wilson

“The Detective of Dreams” copyright © 1980 by Gene Wolfe

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Portions of lyrics from “Light My Fire,” words by The Doors, © 1967, Doors Music Co., are reprinted by permission of the authors and publisher.

Portions of lyrics from “I’m So Afraid,” copyright © 1975 Gentoo Music Inc. All rights for the United States and Canada administered by Warner-Tamerlane Publishing Company. All rights reserved. Used by permission.

To Lurton Blassingame, with admiration and affection and Deborah Wian, for all kinds of good reasons

I would like to express my warmest thanks to Alan Williams, for his enormously helpful and intelligent editorial input on this book.

Table of Contents

Introduction

Kirby McCauley

The Late Shift

Dennis Etchison

The Enemy

Isaac Bashevis Singer

Dark Angel

Edward Bryant

The Crest of Thirty-Six

Davis Grubb

Mark Ingestre: The Customer’s Tale

Robert Aickman

Where the Summer Ends

Karl Edward Wagner

The Bingo Master

Joyce Carol Oates

Children of the Kingdom

T. E. D. Klein

The Detective of Dreams

Gene Wolfe

Vengeance Is

Theodore Sturgeon

The Brood

Ramsey Campbell

The Whistling Well

Clifford D. Simak

The Peculiar Demesne

Russell Kirk

Where the Stones Grow

Lisa Tuttle

The Night Before Christmas

Robert Bloch

The Stupid Joke

Edward Gorey

A Touch of Petulance

Ray Bradbury

Lindsay and the Red City Blues

Joe Haldeman

A Garden of Blackred Roses

Charles L. Grant

Owls Hoot in the Daytime

Manly Wade Wellman

Where There’s a Will

Richard Matheson and Richard Christian Matheson

Traps

Gahan Wilson

The Mist

Stephen King

Afterword

Kirby McCauley

Editor’s Notes

Kirby McCauley

A Conversation with Kirby McCauley

Conducted by Kealan Patrick Burke

Introduction

Kirby McCauley

In more ways than one, the late August Derleth is responsible for the existence of this book.

Back in 1955—when I was in my early teens—my life was permanently and happily altered when I discovered Arkham House, a small publishing firm headed by Derleth based in the village of Sauk City, Wisconsin. Arkham House specialized (and still does) in books of macabre and fantasy fiction, starting up in 1939 with publication of a 1200-copy edition of a large omnibus of H. P. Lovecraft’s stories entitled The Outsider and Others, which various New York publishers had declined to bring out. Against many negative proclamations, including those of Edmund Wilson, who referred to Lovecraft’s stories as “hack work,” Derleth campaigned tirelessly for over thirty years to help gain Lovecraft the kind of serious literary recognition he now enjoys.

But Derleth didn’t stop with Lovecraft. Before his death, in 1971, he published about a hundred books, including first ones by such notable American fantasists as Ray Bradbury, Robert Bloch, Fritz Leiber, and Carl Jacobi. And from Britain he brought over quality works by such distinguished figures as L. P. Hartley, William Hope Hodgson, Walter de la Mare, A. E. Coppard, H. R. Wakefield, Lord Dunsany, Arthur Machen, and Algernon Blackwood. Derleth bound every book he published in handsome black cloth, stamped them with gold lettering, and usually jacketed them with tasteful and striking dust wrappers. His books were good—and they looked it.

Derleth brought out dozens of excellent books—volumes of poetry, anthologies, novels, and story collections—which have never, I believe, been equaled in content or lasting impact by any other single publisher who has tried his hand more than occasionally with the literature of terror and the fantastic. It is true that certain houses brought out the major offerings of a few important writers in the field—Alfred A. Knopf and his list of Machen, de la Mare, and Dahl, come admirably to mind—but only in a context of general publishing, mixing fantasy works with non-fantasy works and lacking Derleth’s sensitive focus, which can help an author to endure in a bookselling market increasingly inclined to categorization.

There is a magic about one of Derleth’s three thousand-copy edition books of the 1940s and ’50s which excites the sophisticated devotee of fantasy fiction far more than almost any best-selling supernatural horror novel of the 1970s. The magic arises out of Derleth’s superb taste and aspiration to publish the best he could find, with no particular aim at the commercial jackpot. Derleth set out to prove—and did—that there is an abiding place in publishing for quality supernatural fiction, and he largely proved it with the hard-to-sell and unfashionable form of the short story, collections of which most publishers do with great reservation, if not downright sour looks on their faces. Year in and year out, Derleth brought out remarkably good books of stories which, after they have gone out of print, are eagerly purchased by connoisseurs, for price

s ranging up to five hundred dollars. Such enthusiasm by a relatively small, ardent band of collectors does not necessarily signal quality or assure posterity, but I venture to say that at least a few of Derleth’s productions, very likely the books of Lovecraft’s fiction and Ray Bradbury’s remarkable Dark Carnival, will stand the test of time.

Derleth did it. He established that there was a permanent place for short fiction of the macabre variety. He was an inspiring force for aficionados of good fantasy fiction and for them the very name Sauk City, in its time, conjured up feelings of reverence. I think, too, he paved the way to some extent for the arrival of quality novels of the supernatural—such as those by Ira Levin, Robert Marasco, John Farris, Stephen King, and Peter Straub—to do well by any standard of book sales. And he certainly made the road to publication for the book you now hold in your hands an easier one to travel.

So, without knowing it, Derleth started me on the course to this book. And it was brought full circle over dinner one night with Anthony Cheetham, the publisher of Futura Publications Limited in England, who suggested I edit an anthology of new stories of horror and the supernatural for him to publish, which we could in turn arrange to have published elsewhere around the world. He liked my only other anthology of original stories, Frights, and seemed to feel I was the person to do a more ambitious similar volume for him. At first I was flattered by his offer, but reluctant to accept, because my feeling was, and still is, that people who edit too many anthologies tend to go stale in their selections.

But as the conversation went on, it struck me: why not try to assemble an anthology with the same scope and dynamism of Harlan Ellison’s Dangerous Visions, but in the supernatural horror field? Ellison’s anthology, for those unfamiliar with it, is a two hundred thousand-plus word anthology of new (in 1967) stories of science fiction. Ellison, however, carefully pointed out that his book contained stories of “speculative fiction,” tales which weren’t shackled by the bonds of strict category, market demands, or editorial taboos. Ellison went after stories that had some roots in science fiction tradition, but which would break new ground, say and do things in new and varied and daring ways. He succeeded brilliantly with both critics and readers. I suggested to Cheetham that we attempt a gambit based in similarly adventurous (though less revolutionary) ambitions, a large book centering on the tale of terror and fantasy. Cheetham liked the notion immediately and promised to back me up in every way feasible—a promise he has splendidly carried through on.

The next step was to find stories. I approached by letter or telephone nearly every writer living who had tried his or her hand at this type of story and whose writing I like personally. Predictably enough, some were able to respond with stories, some were not. I sorely miss here the presence of Jack Finney, Roald Dahl, Elizabeth Jane Howard, Ira Levin, Bernard Malamud, John Farris, Peter Straub, Julio Cortazar, and Nigel Kneale, to name only some. I did what I could to gain contributions from most of the best living practitioners of this kind of story. In addition, I deliberately sought variety, stories ranging wide across the horizon of fantasy fiction. Nothing seems to me more boring than an anthology in one key, having similar backdrops or styles, or which are all variations on a narrow theme. I set out to offer as many of the subjects and moods and general directions the fantastic tale has tended traditionally to take as I could, but hopefully in imaginative, fresh ways.

The pursuit of individual contributions was not without interesting aspects. For example, Stephen King had mentioned to me a year or more before a general idea he had for a story, and I reminded him that it interested me. It sounded just like the kind of story I hankered to have in the book and he phoned one day to say the idea was starting to jell in his mind. A week or so later he called to say the story was under way and looking to run a bit longer than he had originally thought. Would, he asked, twenty thousand words present a space problem? I replied no, my interest heightening. The following week he called to say he had about seventy manuscript pages done—already twenty thousand words or better—but that the end was not in sight. A few days later he called to say that the manuscript was up to eighty-five pages. Soon, another call, and it was over a hundred—and still growing, as was my excitement, of course. And finally the end came: 145 manuscript pages, or about forty thousand words! What King had felt originally to be a novelette of perhaps fifteen thousand words became a novella of forty thousand. I expected an ordinary-length story and ended up with a short novel by the most popular author of supernatural horror stories in the world.

Editing this anthology also provided me with an opportunity to meet Isaac Bashevis Singer. I saw him in his Upper West Side New York apartment on a hot, late spring day in 1978, only a few months before the announcement of his Nobel Prize. He was a gracious and friendly host and it was an hour and a half I shall never forget. Nor will I forget a remark Mr. Singer made in answer to my question as to why he writes so often about demonic and supernatural happenings. He replied, with no hesitation: “It brings me into contact with reality.” Mr. Singer’s arresting answer speaks of the tip of the iceberg well, I think. And so did Stephen King when he once replied to an interviewer who asked why he writes about fear and terrible manifestations: “What makes you think I have a choice?”

In their own ways, I think Messrs. Singer and King were acknowledging the dominating influence of the subconscious on such stories. Of course all art has its origin in the subconscious, but I believe the uncanny tale retains a stronger foothold there, in effect as well as origin. Robert Aickman, who has written thoughtfully and eloquently on the subject of the supernatural story—or “ghost story” as he prefers to call it—has observed:

The essential quality of the ghost story is that it gives satisfying form to the unanswerable; to thoughts and feelings, even experiences, which are common to all imaginative people, but which cannot be rendered down scientifically into “nothing but” something else… The ghost story, like poetry, deals with the experience behind the experience: behind almost any experience… They should be stories concerned not with appearance and consistency, but with the spirit behind appearance, the void behind the face of order.

I believe Aickman couldn’t be more accurate. In reading such stories our goal is more that of mysterious encounter than the prize of resolution or clear moral point. At its best, the tale of the fantastic can convey experiences of a high and exhilarating order because it draws on the power of subconscious truth in both writer and reader, acting as a kind of channel to our submerged self, to that largest part of ourselves we can never fully know, but nevertheless feel. Graham Greene once wrote in appreciation of this effect in an essay on the stories of Walter de la Mare: “…we are wooed and lulled sometimes to the verge of sleep by the beauty of the prose, until suddenly without warning a sentence breaks in mid-breath and we look up and see the terrified eyes of our fellow-passenger, appealing, hungry, scared, as he watches what we cannot see—‘The sediment of an unspeakable possession.’” In contrast to the part of our life devoted to tedious facts and endeavors, it is that contact with the indefinable that can be so satisfying.

A final thought: the tale of horror is almost always about a breaking down. In one way or another such stories seem concerned with things coming apart, or slipping out of control, or about sinister encroachments in our lives. Whether the breakdowns are in personal relationships, beliefs, or the social order itself, the assault of dangerous, irrational forces upon normalcy is a preeminent theme of the horror story. Perhaps this kind of story has always been popular because, no less than our forebears, we live in a world where goodwill and reason do not always triumph, as our daily newspapers constantly remind us. There may well be no permanent escape from the inner and outer darkness that troubles us all, but in its way the tale of terror and fantastic encounter mitigates our fears by making them subjects of entertainment. Who is to say that is a bad thing?

—Kirby McCauley

New York City

The Late Shift

They were driving back from a midnight screening of The Texas Chainsaw Massacre (“Who will survive and what will be left of them?”) when one of them decided they should make the Stop ’N Start Market on the way home. Macklin couldn’t be sure later who said it first, and it didn’t really matter; for there was the all-night logo, its bright colors cutting through the fog before they had reached 26th Street, and as soon as he saw it Macklin moved over close to the curb and began coasting toward the only sign of life anywhere in town at a quarter to two in the morning.

They passed through the electric eye at the door, rubbing their faces in the sudden cold light. Macklin peeled off toward the news rack, feeling like a newborn before the LeBoyer Method. He reached into a row of well-thumbed magazines, but they were all chopper, custom car, detective and stroke books, as far as he could see.

“Please, please, sorry, thank you,” the night clerk was saying.

“No, no,” said a woman’s voice, “can’t you hear? I want that box, that one.”

“Please, please,” said the night man again.

Macklin glanced up.

A couple of guys were waiting in line behind her, next to the styrofoam ice chests. One of them cleared his throat and moved his feet.

The woman was trying to give back a small, oblong carton, but the clerk didn’t seem to understand. He picked up the box, turned to the shelf, back to her again.

Then Macklin saw what it was: a package of one dozen prophylactics from behind the counter, back where they kept the cough syrup and airplane glue and film. That was all she wanted—a pack of Polaroid SX-70 Land Film.

Macklin wandered to the back of the store.

“How’s it coming, Whitey?”

“I got the Beer Nuts,” said Whitey, “and the Jiffy Pop, but I can’t find any Olde English 800.” He rummaged through the refrigerated case.

“Then get Schlitz Malt Liquor,” said Macklin. “That ought to do the job.” He jerked his head at the counter. “Hey, did you catch that action up there?”

Dark Forces

Dark Forces